L’articolo di Barbara Zorman, che riflette sulla letteratura slovena per bambini e ragazzi, è stato pubblicato su Andersen n.410 e nasce dalla collaborazione con la rivista Otrok in knjiga, con il festival Prevodni Pranger, il Centro di Illustrazione e la sezione slovena di IBBY. Condividiamo sul nostro sito la versione in inglese, per accompagnarvi nella scoperta della letteratura del Paese Ospite di Bologna Children’s Book Fair (8-11 aprile 2024). Sostieni la rivista Andersen e abbonati ora!

1. It is deeply rooted in Slovene oral tradition.

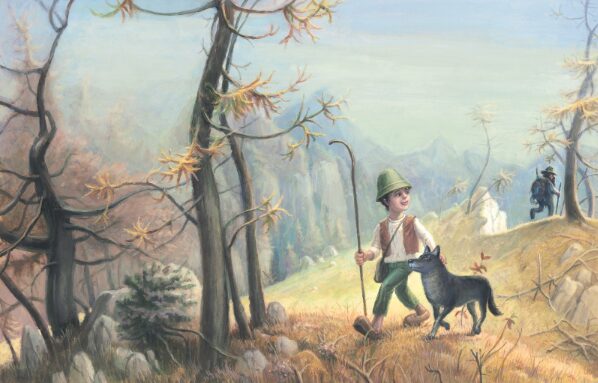

The rise of Slovene children’s literature went hand in hand with the nation-building movement which valued oral tradition above all else. The first Slovene superhero, Martin Krpan (1858, literary journal Slovenski glasnik) – a self-willed salt-smuggler with herculean strength who rescued the Emperor and Vienna from mortal danger – was created by Fran Levstik from folk narratives and was published in 1917 as the first original Slovene picturebook. Fran Milčinski selected ten subjects from old Slovene ballads and transformed them into the first collection of Slovene literary fairy tales Pravljice (1911) so that Slovene children would not only have to read poor translations of the Grimms’ fairy tales. Some of the tales from this collection would make contemporary parents’ hair stand on end, since in addition to the story of the tenth daughter who, according to tradition, has to leave home and restlessly and haplessly wander the world, it also includes the tale of the fairy mother who takes her baby from home at night and refuses to tell her horrified husband where she has left the child. The folklorist Milko Matičetov created a bilingual fairy tale collection (in literary Slovene and the Resian dialect) entitled Zverinice iz Rezije (“Animal Tales/Little Beasts from Resia”, 1973) based on his tape recordings of tales collected in the remote Resia valley (dolina Rezije/Val Resia) bordering Slovenia in the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region of Italy. In this collection everything that can happen to a living human happens to a fox, wolf or hare. The storytellers whom Matičetov recorded did not shy away from “serious” topics such as exploitative relationships, the use of cheating and deceit to achieve one’s goals, yet they recreate their animal characters with touching love and respect. Josip Vandot created his literary character Kekec (1918), a fearless boy of eight, who later became the most famous Slovene film hero of all time, on the basis of Alpine folk tradition.

Illustrazione di Polona Lovšin da Deklica z vžigalicami (da Hans Christian Andersen), Sanje, 2021

Anja Štefan, a writer (Mišji ženin “The Mouse’s Groom”), poet (Drobtine iz mišje doline “Tunes from Mousedale Dunes”), playwright (Zajčkova hišica “A Little Hare’s House”), folklore collector and editor established Ljubljana storytelling festival in 1997; every spring, the festival draws large adult and young audiences with a diverse selection of folk content and various Slovene and foreign storytellers. Irena Cerar also works in the folklore collecting and popularising tradition, which she also combines with hiking and exploring the Slovene countryside, as in, for instance, her book Fairy Trails of Slovenia, where she makes the retelling of a folktale part of a family outing.

LEGGI ANCHE: Una biblioteca slovena a Trieste

2. Slovene illustration might appear challenging to readers whose visual culture has been acquired mainly by visual fast food, i.e. glittery stereotypical pictures.

In actual fact, the art of Slovene illustrators is so diverse that newcomers to visual art can take to it just as well as connoisseurs.

In the second half of the twentieth century a group of female illustrators known as the “fairy tale artists” (Jelka Reichman, Marlenka Stupica, Marjanca Jemec Božič, Ančka Gošnik Godec, among others) gained particular prominence, in large part thanks to the harmonious and cheerful tones of their illustrations. Comics noted for their humour – such as those of the authors Marjan Manček, Božo Kos, Miki Muster and Kostja Gatnik – also came on the scene in the seventies. The contemporary comic strip is represented by the magazine Stripburger and the artists Tomaž Lavrič, Matej de Cecco, Tanja Komadina and others.

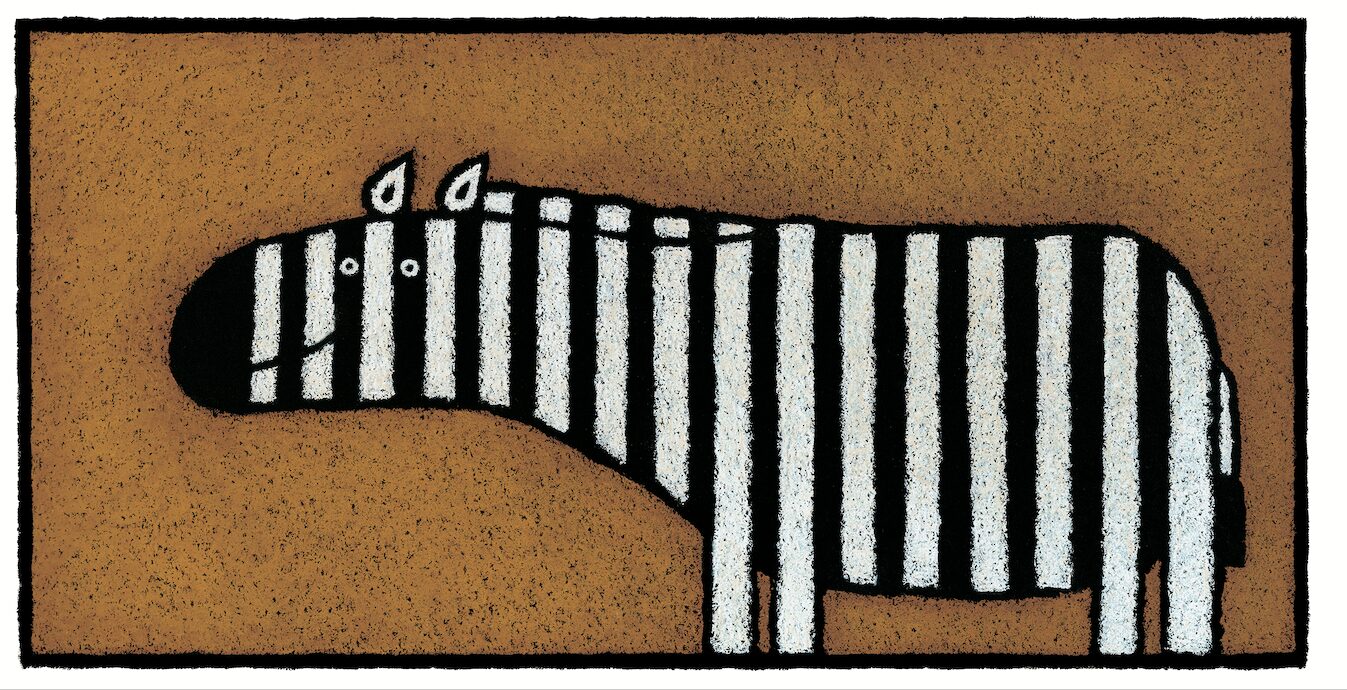

Illustrazione di Lila Prap, tratta dal libro Perché? (San Paolo)

Center ilustracije (the Centre of Illustration) acts as a focal point and creative space for contemporary Slovene illustrators; among those who cater for the youngest age range, four artists in particular stand out: Lila Prap (known for her abstract animals which radiate from the page with their rich texture drawn in dry pastel) as well as Ana Zavadlav, Andreja Peklar and Maja Kastelic. The last two illustrators have received acclaim for their picture books without words; Andreja Peklar’s Ferdo, veliki ptič (“Ferdo, the Big Bird”) was among the finalists in the Silent Book Contest at the 2015 Bologna Book Fair. The illustrators Zvonko Čoh, Polona Lovšin, Alenka Sottler, Damijan Stepančič, Peter Škerl, Ana Maraž, Marta Bartolj, Samira Kentrić and others cater for school age children and adolescents.

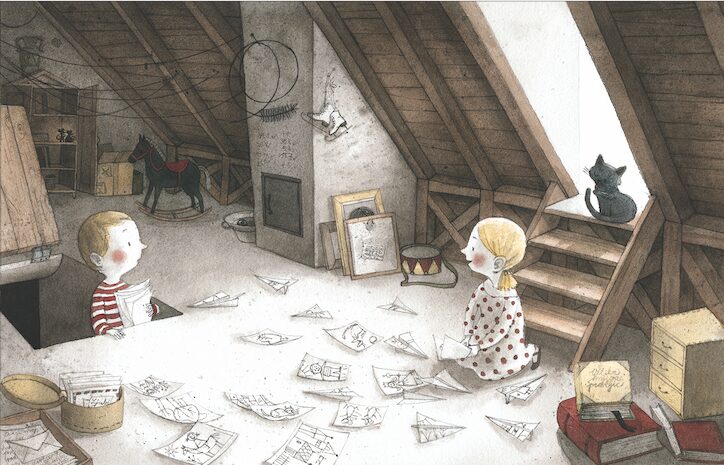

Illustrazione di di Andreja Peklar, da Ferdo, veliki ptič, KUD Sodobnost International, 2016

3. Slovene poets take wordplay extremely seriously, so poems written for children are not in a category apart from poems for adults; what’s more, the poets who write for children are never condescending or protective towards them. Oton Župančič’s Ciciban (1915) is still today one of the most popular poetry collections for children; the poems draw on nursery rhymes or lullabies and are full of onomatopoeic rhythms. Originally an affectionate nickname for the poet’s own son, Ciciban has become a general word for a preschool age child and is also the name of the most popular magazine for children aged 6-8. Mira Voglar created a special form of poetry for children – Bibarije – which incorporate finger games and exercises into short rhythmical poems. Slovene poetry for children and young adults flowered in particular during the modernist period; poets such as Dane Zajc, Boris A. Novak, Tone Pavček, Kajetan Kovič, Niko Grafenauer, Miroslav Košuta, Saša Vegri and others come closer to a child’s perspective in the sense of wonder that they convey at the sound and rhythm of words. Contemporary poets who write for children include Anja Štefan, Peter Svetina, Andrej Rozman Roza, Marko Kravos, Bina Štampe Žmavc, Barbara Gregorič.

Illustrazione di di Alenka Sottler da Drobtine iz mišje doline (di Anja Štefan), Mladinska knjiga, 2017

4. In the last couple of decades there are more characters in children’s/youth literature that promote diversity and inclusion, and who also tackle difficult and taboo subjects.

Svetlana Makarovič has already from the 1970s been creating fairy tale characters who fight for the right to be free and unconventional. Her creations such as Sapramiška (Sapra the little mouse), Pek Mišmaš (Mišmaš the baker), Kosovirja on a flying spoon are today commonplace in Slovene culture. Unconventional characters are also a feature of Peter Svetina’s prose, who was twice a finalist for the Anderson award. His characters are unusual in terms of their species (e.g. porcupine or bison), their names (e.g. Genadij, Nikozija) as well as in their deeds. Mrožek (Little Walrus), for instance, refuses to cut his nails; Mr Feliks has his own rules for living in a place, sports competition and even love … Svetina’s prose is based on play and nonsense – two principles which Ela Peroci introduced to children’s prose fiction in the 1950s.

LEGGI ANCHE: Ana Zavadlav, illustratrice di copertina per Andersen n.410

Barbara Hanuš is the author of numerous multilingual picture books which showcase Slovenia and encourage interculturalism. Aksinja Kermauner brings the world of the blind and partially sighted closer to fully sighted children through humour and empathy. The best-known character in her tactile picture books is Žiga špaget (“Žiga spaghetto”); he escapes from a saucepan, where his brothers are being cooked, and sets out to discover the world. Gaja Kos challenges stereotypes about appearance and behaviour in her series of books about the Grdavši (“Ugglings”) and shows what it is like to live with diversity (Obisk “The Visit”). Helena Kraljič tells the experience of children with Down’s syndrome, asthma and dyslexia. Majda Koren writes about children who have to confront parents’ divorce and alcoholism (“Mihec”) and Lela B. Njatin converts the typical animal fairy tale into a first-person narration about the granny’s peculiar transformation (possibly caused by dementia) which ends with her disappearance (Why Granny is Angry).

Illustrazione di di Maja Kastelic da Deček in hiša, Mladinska knjiga, 2015

Quite a few picture books seek to help children cope with unpleasant feelings. Miha Mazzini tackles in an interesting way in his picture book Zelena pošast (“The Green Monster”) the proverbial Slovene envy, which is even said to be an obstacle to Slovene national entrepreneurship. In her picture books for the youngest children, Nina Mav Hrovat shows how to overcome the fear of the unknown and the loss of one’s closest and dearest as well as how to deal with intolerance; she also jokingly plays with the concept of intrusive thoughts. Jana Bauer in her picture book Kako objeti ježa (“How to hug a hedgehog”) humorously describes the Hedgehog’s growing desire to be hugged. Ida Mlakar in a series of stories about the piglets Biba and Gusti touches upon coming to terms with feelings of anger and sadness, and in her picture book Tu blizu živi deklica “Close to here”) tackles the issue of invisible and neglected children.

Books for teenagers – for instance those by Anton Ingolič and later Slavko Pregl – have already since the 1960s been tackling problems faced by young people. Contemporary writers have foregrounded the representation of sexual identity (e.g. Suzana Tratnik, Janja Vidmar, Brane Mozetič), various forms of dependence (Nataša Konc Lorenzutti: Gremo mi v tri krasne “Going to the Back of Beyond”), suicide (Mateja Gomboc: Balada o drevesu “The Ballad of the Tree”), peer-on-peer violence (Neli Kodrič Filipič: Solze so za luzerje “Tears are for Losers”), neurodiversity, marginalisation (Vinko Möderndorfer: Kit na plaži, Sončnica “A Whale on the Beach”, “The Sunflower”) and migration amongst other topics.

5. Contemporary prose for teenagers presents numerous fictional worlds recreated from our knowledge of history and nature. The sagas Ognjeno pleme ”Fiery Tribe” (Igor Karlovšek), Zgodbe s konca kamene dobe “Stories from the End of the Stone Age” and Zgodbe Vojvodine Kranjske “Stories of the Duchy of Carniola” (both by Sebastjan Pregelj) make use of objects, facts and places dating variously from the time of the Slavic migrations, the time of the pile dwellers in the Ljubljana Marshes who used the oldest known wooden wheel with an axle in the world (approximately 5,200 years ago) as well as from the turn of the modern era, in order to transport readers back to exciting adventures of times past. The contemporary fantastical landscapes of Maša Ogrizek and Špela Frlic emerge from the magical forest (trees cover three fifths of Slovenia) and from the diversity of the birds – Slovenia is remarkable for the large number of plant and animal species it hosts given its small size. Irena Androjna in her novel Modri Otok (“Blue Island”), which has been included on the White Ravens list of recommended children’s and youth literature, creates a fantasy world where Mediterranean nature or a mythologised Mediterranean is interwoven with ecological sensibility.

Illustrazione di di Zvonko Čoh, da Kekec

in Bedanec (di Josip Vandot), Mladinska knjiga, 2001

6. In the past eighty years various innovative institutions have developed for the promotion and dissemination of children’s literature. The major Slovene publisher Mladinska knjiga has since 1945 been dedicated to the publication of Slovene and translated children’s and youth literature, and the publisher’s artistic editors have ensured that there has been a great variety of high-quality illustrations, which amongst other things is evident in the cult collection for the youngest age group, Čebelica “Little Bee” (from 1953). Other publishers such as Aristej, Didakta, Eduka, Malinc, Miš, Morfem, Sanje, Sodobnost, Pivec, Zala also fulfil their mission by publishing literature for children and young adults.

There is also an exceptionally well-developed system and network of children’s libraries. The Centre for Youth literature and Librarianship of the Ljubljana City library has been developing a book-based educational programme for more than half a century now, including popular manuals containing quality texts for children and young adults (the Manual for Reading Quality Youth Books) as well as the Golden Pear Quality Badge and the Golden Pear Award. The Slovene branch of IBBY, which is one of the most active branches of this international organisation, is also based in the Ljubljana City Library. The Maribor City Library has since 1972 published the journal Otrok in knjiga (“The Child and the Book”), which specialises in children’s literature, literary education and the book-related media. The journal is also involved in the Večernica award, which is given for the best work of youth literature published in the previous year. The award is the highlight of the annual meeting of Slovene youth literature writers Oko besede (“the Eye of the Word”) literary festival. The Kristina Brenk Original Slovene Picture Book Award and the Desetnica Award are also important.

The Reading Badge, the aim of which has been for 64 years to promote leisure reading amongst all sections of the population, is a phenomenon in its own right; every year more than 140,000 children and more than 7,000 reading mentors take part in the movement. The translation of world children’s literature into Slovene is also of the highest quality and is up to date.

Illustrazione di Damijan Stepančič da Kako zorijo ježevci

(di Peter Svetina) Miš, 2015

7. Youth literature in Slovene is interdisciplinary: it is connected to other arts as well as with science. The literary works of contemporary writers are regularly performed in the Ljubljana and Maribor puppet theatres. Slovene youth literature is also connected to animated film (Animateka) and music (Maček Muri, Repki, Enci benci Katalenci). The Slovene hands-on Scientific Centre House of Experiments is adorned with illustrations by the well-known children’s author Božo Kos. The first original Slovenian non-fiction books for children were published in the early 19th century but in recent years some particularly informative as well as entertaining examples of this genre have been published. Sašo Dolenc’s Od genov do zvezd (“From Genes to the Stars”), for instance, seeks to raise children’s interest in scientific discoveries. Tina Bilban’s 50 abstraktnih izumov (“50 Abstract Inventions”) brings philosophical concepts to children in a humorous way. The publisher Založba Aristej brings learning in the humanities and social sciences – which are often overlooked in school textbooks – to young readers in the popular science Pojmovniki (Books of Concepts) collection and has published books on such topics as migration, religion and the media.

Translated by Oliver Currie